We Travel by Issa Makhlouf

Weekend Poem: We Travel by Issa Makhlouf

By Jenny Bhatt April 11, 2014

Every country in this world has been shaped by waves of new immigrants tumbling over its shores for centuries. Now, in the 21st century, we are all itinerant travelers, whether we’re plane-hopping indifferently over vast oceans to reach distant lands or escaping to imaginary places through books or, even, surfing the depths of the internet from the comfort of our couches. And, whether we travel to seek other states, other lives or other souls (to paraphrase Anaïs Nin), often, our real reasons for wanting to leave one home to make another somewhere else are as opaque or vague to us as they might be to the others in our lives.

Today’s poem describes some of those myriad reasons and ways that we seek out and travel to other places. However, the bigger issue that it explores is our sense of self, our identity, as we uproot ourselves from one place to settle in another. And, how, as we seek out new experiences and adopt new cultural layers, they can cover or alter that sense of self/identity till we don’t recognize ourselves any more.

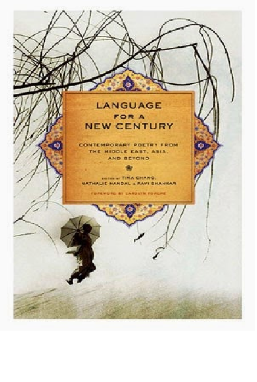

Our poet today, Issa Makhlouf, is a Lebanese author, poet and translator, who writes in both Arabic and French. Currently, he lives and works in Paris, France. There aren't too many English translations of his works, it seems. That said, the odd anthology of English translation poetry, like ‘Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from the Middle East, Asia and Beyond‘, where I found this prose poem, does, thankfully, help to bring poets like him to light.

A few words on this anthology, which the award-winning poet, translator, editor and activist, Carolyn Forché, describes as “an unprecedented collection” in the foreword. Primarily, this is because of the range of poems it brings together: “lyric poems, ghazals, narratives, dramatic monologues, concrete poems, epistolaries, poems of confession and address, odes, elegies, postcards, inventories, haiku, and the less familiar Japanese form, zuihitsu.” Published in 2008, the book began as a project between three poets – Tina Chang, Nathalie Handal and Ravi Shankar — as a response to the issues of cultural identity, particularly for people of Middle Eastern and Asian descent, that had flared up as a result of the bombings of September 11, 2001. This hefty anthology contains post-WWII poems translated into English (many, for the first time) from over forty different languages and written by some four hundred poets (both emerging and established) originating from sixty-one countries and/or territories. There are nine sections or themes to how the poems have been organized: “childhood, identity, the avant-garde, politics and oppression, mystery, war, homeland, mortality and eros.” This poem comes from the section titled ‘Parsed into Colors’ and relates to identity (each section is titled after one of the poems it contains).

From the start, the warm, collective “we” invites us to share the speaker’s thoughts. The first verse is filled with references to our early lives and the need to either get away from that phase or to retrieve it — birth, childhood, etc. There is some beautiful play on words here with “in search of births unconceived” and “so that unfinished alphabets complete”. And, that final sentence about how we travel to re-create our destinies is painted rather beautifully: “We tear up destinies and disperse their pages in the wind before we find—or fail to find—our life story in other books”

With the second verse, the speaker keeps the thread about destinies going. But, this verse starts with an inventory of the things we travel “towards” rather than “away from”, as if we are en route now and looking forward in anticipation of the new land, filled with promises. And, then, as with the previous verse, the speaker ends with another poignant image. This time, it is the mother left behind, who never can forget the child who has left: “We travel far away from mothers who light the candle of absence and thin the crust of time whenever they raise their hands to heaven.”

And, as before, the third verse continues the previous thought, expanding it to describe the leaving behind of parents as they grow old without our seeing how time affects them. Despite that, as we travel, we find or re-find love. The new country soon becomes as dear to us as our homeland, so that, when we do return to that old homeland, we’re like immigrants there too — our travels have made us “immigrants everywhere”. And, yet, there is joy to be had in such winged flight — the sense of freedom that a new and wider horizon gives us. Crossing such expanses of air and water almost makes us feel like we’re cheating or, as the speaker says, mocking time, because our sense of time itself changes. Just like, when we’re on an actual long-distance flight, we’re not in really in the time zone of the place we’ve left behind or the place we’re going to — at least for the duration. And, even when we land in a different physical time zone and adjust our minds and bodies to it, there is, often, an inexplicable sense that the place left behind has remained suspended in the hour that we left. So that, if, or when, we do eventually return to find that it has indeed marched right along with time too and not stood still waiting for us exactly as we left it, we are somewhat taken aback.

The final verse is the saddest here. The speaker turns to a darker theme, though, of course, this has been foreshadowed in the earlier verse. The act of travel is now described as similar to that of a clown going from village to village, trying to entertain the children, but falling short. And, how, though we may be trying to cheat death (physical or metaphorical), it never stops trailing us all along — for all things must end, regardless of how many new beginnings they get. We keep going to places, searching for newer, better versions of ourselves. And, just like a plant suffers stress and damage from frequent uprooting and transplanting, our sense of self, too, can suffer from not having strong roots in any one place. The speaker puts this in rather bleak terms: “… we can no longer find ourselves in the places we travel to; until we are lost and nobody can find us anymore.”

Now, though the poem does end on this pessimistic note, we know that the flip side is not ideal either. When we, for fear of losing our ethnic identity or due to a fear of or lack of trust in a new culture, cling to our own communities and do not assimilate, we deprive ourselves of many wonderful experiences and contributions. Some of the most interesting and amazing innovations and developments have happened when cultures have intersected and mingled socio-culturally. Such fertile cross-pollination of ideas, values and habits alter both respective cultures for the better (almost always). As with almost everything in life, what is needed is a balance between the old and the new so that we may keep our deeply-rooted sense of self, yet be always open to what is offered or available to us. Easier said than done, I know. But then, closing ourselves off and pining for the old homeland is to defeat the very purpose of seeking out the new, is it not?

We Travel

We travel to go far away from the place of our birth and see the other side of sunrise. We travel in search of our childhood; of births unconceived. We travel so that unfinished alphabets complete. Let farewell be imbued with promises. Let us move far away like the twilight that accompanies us and bids us farewell. We tear up destinies and disperse their pages in the wind before we find—or fail to find—our life story in other books.

We travel towards unwritten destinies. We travel to tell those we have met that we shall return and meet again. We travel to learn the language of trees that never travel; to burnish the ringing of bells resounding in holy valleys; in search of more merciful gods; to strip the faces of strangers off the masks of estrangement; to confide to passers-by that we are passers-by, too, and our stay in memory and oblivion is temporary. We travel far away from mothers who light the candle of absence and thin the crust of time whenever they raise their hands to heaven.

We travel so we do not see our parents grow old; so we do not read their days on their faces. We travel taking ages unawares; they are wasted in advance. We travel to tell those we love that we still love them; distance cannot overpower our amazement: that exile is as sweet and fresh as our homeland. We travel so that, if we returned to our homeland, we would feel like immigrants everywhere. Thus, suddenly, we shake off our wings, idle porches open unto the sun and onto the sea. We travel until no difference remains between air and air, water and water, heaven and hell. We mock time. We sit and look into the expanding space, watch the waves jump together like children. The sea in front of us leaves between two ships: one of them departs; the other, a paper boat in the hand of a child.

We travel like the clown who moves from village to village with his animals that teach children their first lesson in boredom. We travel to trick death, letting it trail us from place to place. We continue to travel until we can no longer find ourselves in the places we travel to; until we are lost and nobody can find us anymore.

~ Issa Makhlouf, (translated by Najwa Nasr) from ‘Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from the Middle East, Asia, and Beyond‘